It’s Time to Stop Racializing Blood Donation

In 2017, England's blood service defended its procedures amid concerns over the racialization of blood donation. However, the question remains: doesn't this amount to an endorsement of race science?

[Note: A version of this article was originally published by The Good Men Project on May 13, 2022.]

While it is generally accepted that race is a social construct, blood services in countries such as the US, UK and others continue to call specifically for Black blood donors to save Black patients. The unfortunate implication of this practice is to perpetuate the belief that biological race is real and legitimize the troubling ideology of race science. It is difficult to fathom how, well into the 21st century, national blood services remain in the dark ages, irresponsibly promoting the idea of race as biology.

In 2017, there were concerns among some tweeters regarding a racialized call for Black blood donors by England’s blood donation service, NHS Blood and Transplant. Journalist Rose George reports that the head of donor services at NHS Blood and Transplant went so far as to use the phrase “We need black blood.” Following the unease on Twitter about the focus on Black blood donors as opposed to all blood donors, the blood service adopted an excessively defensive position, as illustrated in the following screenshot.

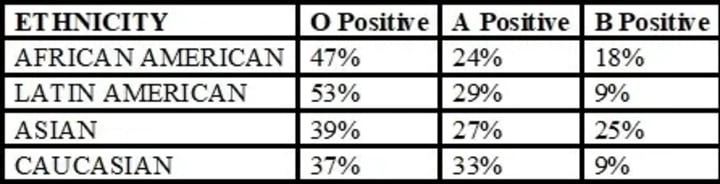

@GiveBloodNHS justified the need for racialized blood donation by over-emphasizing the rarity of the "Ro" blood subtype, which is more common in Black individuals but not exclusive to them. The blood service also implied that patients with sickle-cell disease, who require frequent blood transfusions, can only be helped by Ro blood. Additionally, they insinuated that sickle-cell anemia only affects Black individuals, although this is not the case.

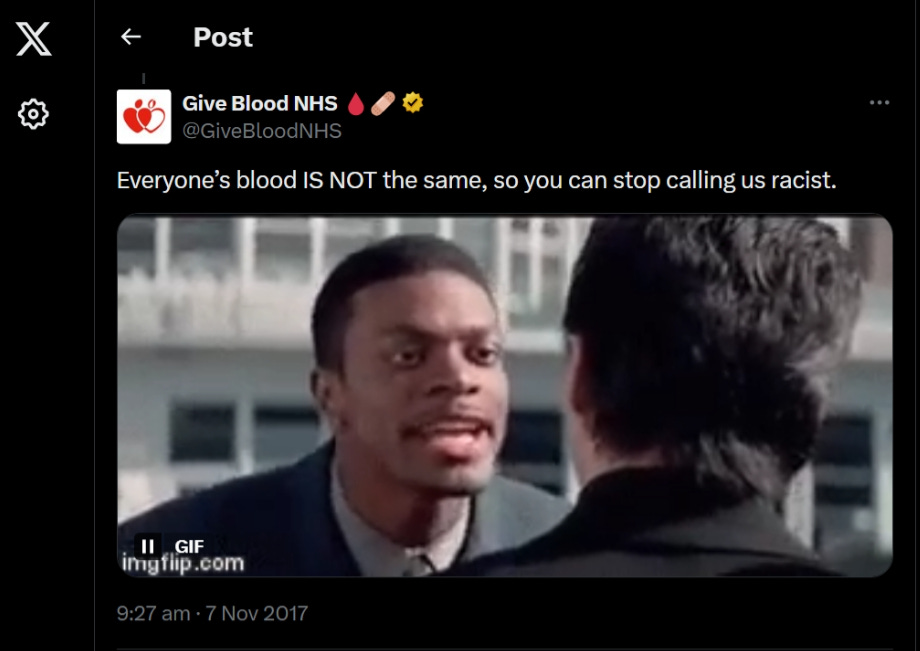

“There are no major ethnic variations among the most common blood types.”

A broader concern is whether the assumption that only Black donors can provide transfusions to sickle-cell anemia patients might be perpetuating the false notion that "race is real. Let's take a closer look at the actual science.

It has been claimed that roughly 20% of Blacks vs 2% of Whites have the Ro blood subtype; however, as far as the author is aware, there are no recent studies that validate this.

While individuals who require frequent transfusions do respond better when the specific blood subtype of the donor is the same, it is important to note that in emergency situations, everyone routinely receives O negative blood, which is regarded as a universal blood group. Thus, if Black patients are as biologically different as the blood service would have us believe, they would not be able to receive O negative blood.

US data indicates that there are no major ethnic variations among the most common blood types, as illustrated by the American Red Cross statistics in the table below.

The English blood service implies that all sickle-cell patients have Ro blood; however, this is not the case.

Contrary to popular belief, sickle-cell anemia (SCA) is not linked to skin color. As noted by scientists at Rutgers University, “the historical spread of the sickle-cell mutation is also apparent among SCA patients of Greek, Portuguese, Sicilian, and other Southern European origins.”

“Why is the blood service implying that Black people who need blood transfusions automatically require Black donors?”

Even if the Ro blood figures are correct (20% of Black people with Ro blood vs 2% of White people with Ro blood), it’s worth critically examining why there would be a specific need for Black Ro donors vs Ro donors of all ethnicities.

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume that 2% of the whole UK population has Ro blood — roughly 1.36 million people in the UK. (The UK population is approximately 68 million.) Let’s also assume that 20% of the UK Black population has Ro blood — roughly 408,000 people. (The UK Black population is only 3% of the UK population.) Here are some questions to consider:

Why target the smaller group of 408,000 Black people with Ro blood vs the bigger, diverse group of 1.36 million people of all ethnicities with Ro blood? Would it not be easier to target people from all ethnicities who actually have Ro blood vs all Black people? (Even if we assume that 20% of Black people have Ro blood, a whopping 80% do not.)

Why is the blood service implying that Black people who need blood transfusions automatically require Black donors? (This simply isn’t the case.)

“While the blood service gives the impression of being politically neutral, its policies and procedures actually serve to stigmatize Black people by focusing on presumed biological differences.“ (Mwamba, 2019)

It is interesting to note that England’s blood service simultaneously describes Ro blood as being “rare,” while also concluding that it’s common enough among Black people to require an exclusively Black blood donation campaign. Unfortunately, nothing positive can be inferred from this; the claim that a) Ro blood is so apparently rare yet b) is common among Black people is problematic because it perpetuates the myth in medicine and science that Black people are abnormal and biologically different from other ethnic groups.

Nseya Mwamba’s research (2019) explores how Canada’s blood service continues to promote ideologies which “racialize and biologize Black populations as different than the norm.” Mwamba argues that while the blood service gives the impression of being politically neutral, its policies and procedures actually serve to stigmatize Black people by focusing on presumed biological differences. This is in keeping with what evolutionary biologist and geneticist, Joseph L. Graves Jr. calls “The Myth of the Genetically Sick African,” i.e., the false idea in science that people of African descent are inherently sicker than non-Africans. It’s also consistent with the concept of “othering,” a process which dehumanizes marginalized groups by obsessing about superficial differences; fostering a “them and us” sentiment among the in-group; and reinforcing social hierarchies between in-groups and out-groups.

Like it or not, the implication that minor differences among ethnic groups are more significant than they actually are is serving to legitimize scientific racism, intentionally or unintentionally. A more constructive approach to increasing the supply of Ro blood would be to target every human being with that blood type, as opposed to fixating on one “racial” group. A unified, non-racial approach to blood donation is more practical; it avoids further marginalization of Black people; and promotes a culture of inclusiveness rather than separation.